What’s your legacy?

It’s clear, at this point if I don't do something,

my legacy will be lots of boxes

filled with mementos.

At my daughter, Dana’s suggestion, that I create a blog of

all my writing and at my daughter, Danielle’s suggestion that Larry and I put

our music and poetry together and create

podcasts, I begin to dig into those old boxes and become

overwhelmed.

What am I to do with

all this stuff?

Maybe it’s the

discovery of an early menopause poem that’s gotten me to thinking.

It’s easy to become overwhelmed and

decide to just let the kids dig through it after we’re gone.

Whose responsibility is it to create

the story, the legacy of one’s life?

Let everyone pick what they want and create whatever story they want?

And what’s left ends up in a garage

sale, or at Calvin Kinnet’s, the local antique/junk dealer.

Frequently I peruse his recent

acquisitions and ponder the story no one wanted to tell.

In the nineties when I read

Carolyn Heilburn’s book,

Writing a Woman’s Life she wrote about the importance of writing one’s life in advance of

living it. I took her serious. I was in my forties and I wrote about how I saw

myself as a writer, an artist, a mother. This mission is what drove many of my

writing practices. Now, that I am

67 it’s time to revisit that mission.

And what better way than looking back, digging in those boxes, and then

looking forward to define my future. At

66, Heilburn said, “Aging's just another word for nothing left to lose.” In the same way that everyone has a

story to tell and it’s important to give it a voice, it’s important that we

mine those stories for the legacy we have to pass down and I’m bound and

determined to not shove those boxes back under the bed.

Bound and Determined

I was in the throes of

missing another cycle. Is that

what the roll around the middle is really about as the tight skirt is more

difficult to zip up and I wonder why I wore girdles at the beginning of puberty

when menopause is when I need them but have out grown the desire?

The roll creases my

jeans, now that I have moved into women’s sizes. Just last week when I called my mom long distance she told

me she found a new brand. It was

information I welcomed but didn’t want to receive.

I was bound and

determined I would never have her big hips or her roll around the middle but

not bound enough to eat less or exercise.

Bound enough to look in the mirror, though, to change my pose to see if,

per chance, it had gone away.

It’s a slow coming that

takes me on to the “I don’t care” and eating more greens as I begin to shop for

looser fitting clothes and more sweats and practice asking for exactly what I

want and make buttermilk coffeecake even when all the nuts sink to the

middle. Do you think I should stir

the batter? ©1993

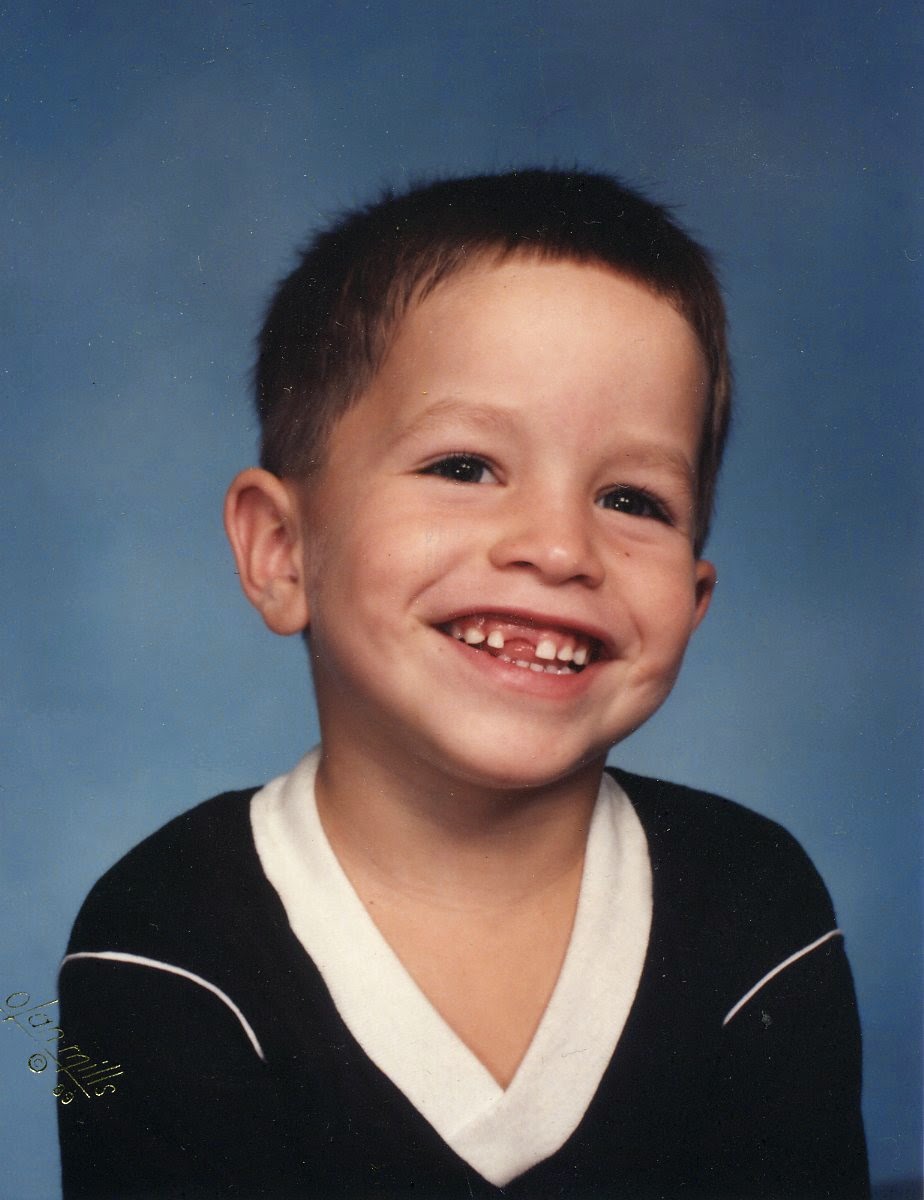

A Bound and Determined Crew

Danielle, Dana, Me and Donnie